The Great Depression brought economic ruin to the United States, with unemployment peaking at 25%. But while cities suffered through breadlines, farmers in the Great Plains faced a different catastrophe: the Dust Bowl. This wasn’t just bad luck; it was a disaster born from short-sighted farming, relentless drought, and the unforgiving geography of the American heartland.

The Seeds of Disaster: Boom, Bust, and Plowing the Plains

The story begins with the Homestead Act of 1862, which lured settlers west with promises of free land. The Great Plains, despite its harsh conditions, seemed ripe for exploitation. Advances in farming technology – McCormick Reapers, steel plows, tractors – made cultivation possible. Wheat prices surged during World War I, driving a land rush. Farmers plowed under nearly 32 million acres of native grassland between 1910 and 1930, believing that “the rains follow the plow.”

This was a fatal miscalculation. The native grasses held the soil together, and the lack of trees left the land exposed to brutal winds. The end of WWI brought collapsing wheat prices, forcing farmers to plow more land in a desperate attempt to offset falling revenue. The rains didn’t follow; instead, a prolonged drought set in by 1933.

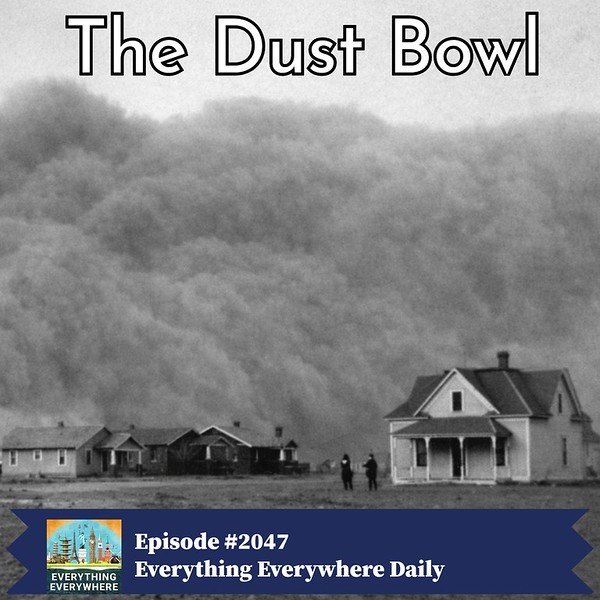

Black Blizzards: When the Sky Turned Black

The result was catastrophic. The plowed soil, stripped of its natural defenses, turned to dust. Massive dust storms, dubbed “black blizzards,” choked the plains. In 1932, there were 14 storms; by 1933, that number jumped to 38. Plants were sandblasted into oblivion, livestock suffocated, and visibility often dropped to zero. One infamous storm, Black Sunday on April 14, 1935, turned the sky black as night and drove temperatures down by 30 degrees in hours.

The storms weren’t just an agricultural disaster. Dust pneumonia killed hundreds, and schools closed as parents kept children indoors. The economic toll was immense: 35 million acres of farmland became unusable by 1934, an area the size of Wisconsin. Another 100 million acres lost most of their topsoil, an area comparable to California.

Exodus and Intervention: The Government Steps In

The crisis triggered mass migration. Nearly 2.5 million people abandoned the Great Plains, packing up what little they had and heading west, often to California. This influx overwhelmed the state, creating shortages and depressing wages. The plight of these migrants became a national symbol of hardship, immortalized in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

Finally, the Roosevelt administration intervened. The National Soil Conservation Service was established in 1935, led by Hugh Bennett, who famously timed a congressional hearing to coincide with a dust storm that reached Washington D.C. The government launched films explaining the disaster’s causes, promoted new farming techniques like contour plowing, and planted over 200 million trees to create windbreaks.

A Legacy of Resilience: Lessons Learned

The Dust Bowl didn’t end until the rains returned in 1940 and government programs took hold. While droughts still plague the Great Plains, the region has never experienced another disaster of that scale. The crisis forced a reckoning with unsustainable farming practices and the brutal realities of the land. The story of the Dust Bowl is a stark reminder that even the most fertile ground has its limits – and that ignoring them comes at a steep price.