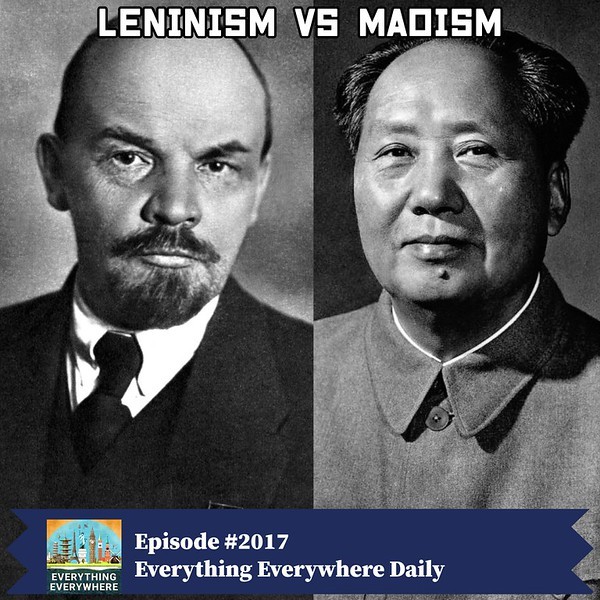

Communism, as an ideology, dominated the 20th century, yet its implementation varied drastically across nations. While many regimes claimed allegiance to Karl Marx’s original vision, the reality on the ground often diverged sharply. This episode explores the key differences between two prominent communist movements: Leninism in Russia and Maoism in China. Both emerged from Marxist theory but adapted to very different conditions, resulting in distinct paths to revolution and governance.

The Foundation: Marx’s Vision

Karl Marx, a 19th-century German philosopher, laid the groundwork for communism with his theories of class struggle. In works like The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital, he argued that capitalism was inherently flawed, destined to collapse under its own contradictions. The core concept: a conflict between the proletariat (workers) and the capitalists (owners) where the former are exploited for profit. Marx believed that this exploitation would eventually drive a workers’ revolution, leading to a classless communist society.

However, Marx also theorized that this revolution would only occur in highly industrialized capitalist economies where the working class was large and politically conscious. He didn’t foresee, or necessarily expect, communism taking root in agrarian societies.

Leninism: Adapting Communism to Russia

The first major communist revolution happened in Russia in 1917, led by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Lenin adapted Marxist theory to Russia’s specific conditions, which were far from the industrialized model Marx envisioned. He developed Leninism, a doctrine emphasizing the need for a vanguard party – a disciplined, elite group to lead the proletariat and seize state power.

This was a critical divergence from Marx. Lenin believed the working class wouldn’t spontaneously develop revolutionary consciousness, so a strong, centralized party was necessary to guide them. The Bolsheviks’ rise to power wasn’t the organic uprising Marx predicted; it was a calculated seizure of control, followed by the establishment of a totalitarian state under first Lenin and later Joseph Stalin. The Soviets, or workers’ councils, were meant to be democratic but were quickly dominated by party loyalists, reinforcing centralized control.

The Soviet Union, formed in 1922, remained under Leninist rule until its collapse in 1991. The justification for this authoritarianism rested on Lenin’s idea that a vanguard was essential to accelerate the transition to communism, even if it meant suppressing dissent and maintaining absolute power indefinitely.

Maoism: Revolutionizing the Peasantry

If Marx would have been surprised by communism in Russia, he would have been utterly shocked by its emergence in China. Maoism, developed by Mao Zedong, took a radically different approach. Unlike Lenin, Mao prioritized the rural peasantry as the driving force of revolution.

Mao’s background as a peasant shaped his ideology. He believed that a communist uprising was achievable only with a revolutionary unit of peasants, not industrial workers. The Chinese Communist Party drew most of its support from rural areas, making it a distinctly agrarian movement.

Mao’s policies, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, were attempts to mobilize the peasantry and transform China into a communist society. Both were catastrophic failures, resulting in mass starvation and social chaos. The Great Leap Forward led to millions of deaths through inept agricultural policies, while the Cultural Revolution plunged the country into turmoil.

Despite these disasters, Maoism dominated China from 1949 until his death in 1976. Like Leninism, it justified totalitarian rule under the guise of revolutionary ideology.

Shared Traits & Divergences

Both Leninism and Maoism shared key characteristics: a belief in the necessity of a Communist Party vanguard, a rejection of spontaneous socialist revolution, and a willingness to use violence to achieve and maintain power. Both systems emphasized strict party discipline, ideological conformity, and the suppression of counterrevolution.

However, they diverged in their social base and strategy. Leninism focused on the urban working class, while Maoism prioritized the peasantry. Lenin envisioned a rapid seizure of state power in cities, while Mao relied on prolonged guerrilla warfare in rural areas.

Beyond Russia and China: Adaptations and Deviations

The communist movements in other countries further deviated from Marx’s original theories. Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito experimented with workers’ self-management, while North Korea under Kim Il-sung developed Juche, an ideology prioritizing national self-reliance and dynastic rule.

In reality, no highly industrialized nation ever underwent a Marxist revolution, proving that Marx’s predictions didn’t unfold as he intended. The common thread across all these communist regimes is that their ideologies were ultimately tools to justify their own power and existence.

The most striking irony is that the regimes claiming to follow Marx’s theories were, in fact, the ones that deviated the furthest from his original vision. The reality of 20th-century communism was not a classless utopia but a series of authoritarian states using ideology to legitimize their rule.